|

| |

|

ANTIQUE BOXES

at the Sign

of the Hygra

2 Middleton Road

London E8 4BL

Tel: 00 44 (0)20 7 254 7074

email: boxes@hygra.com |

Antique Boxes in English Society

1760

-1900

by

ANTIGONE

Tea and Opium |

News

| Buying

| Contact us

| Online History of boxes

| The Schiffer Book | Advanced

Search

|

John Barrow wrote in the Quarterly Magazine of 1836:

"........it is a curious circumstance that we grow poppy in our Indian

territories to poison the people of China in return for a wholesome beverage

which they prepare almost exclusively for us"

The image of tea drinking in England conjures up comfort, cosiness and

eccentricity: idyllic cottages and grand houses, tea gardens and tea dances,

part and parcel of a genteel society indulging in harmless and elegant fun.

Behind this facade of respectability the history of tea is one of the most

sinister chapters of government manipulation the world has ever known. It

can be argued that it was the catalyst, which brought about the expansion

of the British Empire. In the 18th and 19th centuries the use of tea in England

was inextricably and irrevocably interwound with opium, rendering it one

of the two crops whose interdependence yielded vast financial and consequently

political influence.

|

|

A rare Napoleonic prisoner of war straw work box.

The lid is decorated with a straw marquetry picture of the East India

House in Leadenhall Street in London after its late 18th century

transformation from an Elizabethan building into a neoclassical edifice.

Although the Company's vast wealth came from the East, the Company

headquarters were designed in the European neoclassical style.

|

Many an English bank was set up on money earned from opium and tea dealing.

Many grand houses and fortunes were made and sustained by trading opium for

tea. The opium was derived from the poppy grown in British controlled India

for the purpose of selling it to China.

The whole operation was administered by the British East India Company. The

Company was set up in 1600 and it was granted trading rights in India early

in the 17th century by the Mogul Emperor. In 1637 the first Company ships

sailed to China with a view to exploring trading possibilities in the Far

East. China did not allow free range to foreign traders. It allowed them

to stay in the trading quarters, down river from Canton and only during the

trading season. There, the Company established their warehouses and carried

their transactions through the Chinese Hong merchants.

|

|

The events, which culminated in the Opium Wars of 1839-1842, are complex

and confused. Different interests of involved parties often resulted in bungled

outcomes. Here I am only trying to give the essence of the Tea/Opium struggle

so as to enable the reader to realise why Tea was so precious in the late

eighteenth and early nineteenth century.

Tea was deliberately allowed to be hyped so as to provide valuable revenue.

The elaborate social rituals, which were nurtured around tea drinking, were

more to do with money than the appreciation of the fine flavour of the beverage.

These rituals needed beautiful accessories such as Tea Caddies, Teapots,

spoons, strainers, tea gowns etc. to give gravitas to the business of drinking

tea. Many artists and craftsmen turned their hand to creating little treasures

for the tea table. Internal business was thus stimulated and unlike the aftermath

of the opium trade the resulting products from this era of tea drinking are

a beautiful legacy.

Tea was first imported to England from China in the seventeenth century.

It was introduced in small quantities as a precious commodity. It is not

clear when opium was first sold to China, although English traders first

bought it in India in the seventeenth century. It must have been sold much

earlier than the government was willing to admit.

The government of the day saw its chance of augmenting revenue by imposing

heavy import duties on tea, which was perceived to be a rare and precious

beverage. In 1701 less than 70lb of tea was imported rising to about a million

by 1730 and nearing twenty million by the last decade of the century.

As the eighteenth century progressed and demand rose, the inevitable result

was greed for more profits by more people and especially the Exchequer. |

Details: Papier mâchè slope

showing A Tea House in Hong Kong.

The box is inscribed Tea House at Kow Loon.

Kow Loon, which is located on a peninsula across the water from Hong Kong,

had by the middle of the 19th century acquired the reputation of a place

for the negotiation of stolen goods. The English merchants soon spread

their control over this illicit corner of China.

|

Chinese export lacquer tea chest with

scenes of tea trading the interior fitted with metal canisters, circa 1840.

|

In an age of social change opportunists saw tea as a way of profiteering

from a commodity, which after all was hyped with the blessing of the government.

It is not easy to be certain how much tea was sold for. There were claims

of 10 a pound early on but by the end of the eighteenth century it settled

to about 16 shillings per pound. This made it impossible for poor people

to afford and amongst other ways they obtained their tea by buying second

hand leaves from inns. Smuggling and adulteration with amongst other things

dried sheep droppings and cow dung became rife. Even so legitimate imports

continued to rise.

To people who did not know all the machinations of the government it looked

as if the scales of trading had tilted in favour both of China and Holland

from whence a lot of the smuggled tea came to England. Too much coin was

leaving England to pay for the tea and even though the Exchequer was doing

very well out of import duties, there were rumbles of discontent and a concern

that the country's economy was doing less well out of it than it potentially

could.

|

|

Thinkers were beginning to air their views on what they saw as a beverage

of little value-except perhaps for weaning people off the gin. There are

numerous references to tea in literature and diaries of the period. Especially

significant is the mention of tea in satire and caustic verse. The intellectuals

suspected the social manipulation, which was going on in the teacup.

The government of course did not want such a good revenue spinner to disappear

from the English table. Far from it. Tea image and drinking were actively

encouraged by sustaining the social status of the new beverage. On the other

hand it did not seem expedient to let the public know of the opium trade.

This would have created more discontentment.

Mindful of the criticism, both actual and potential, which threatened such

a good revenue spinner, the government of the day set out to create an

alternative way to pay for the tea. Attempts to sell large amounts to America

failed dismally. By the end of the eighteenth century one way forward was

seen to be new markets for British products.

In 1793 an attempt was made to interest the Chinese in British manufactured

goods. A delegation headed by Lord Macartney was sent over with samples of

British wares. The Chinese were not impressed. The ambassadors were firmly

dismissed albeit with impeccable courtesy.

|

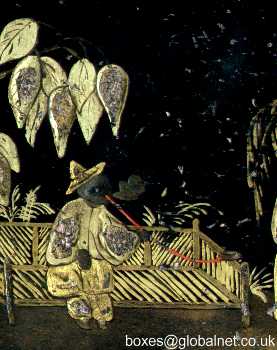

Detail: A sedan chair shaped almost organically This

method of transport definitely beats the bus.

A fine Regency three compartment Penwork Tea caddy

decorated all over with exotic penwork scenes on a sycamore ground . Circa

1815

These Chinoiserie scenes were inspired by tales of the

gardens of the Hong merchants which British traders and diplomats were

allowed to visit whilst in Canton. Such scenes found their way into prints

and books as well as diaries and letters of the period.

|

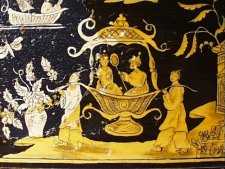

Detail: The tall female

figures with their long feet and large round eyes look European rather

than Oriental. A piece which echoes the Sino-European relationships of

the early 19th century.

A polychromed tea chest painted in a

fluid hand with an exotic scene. The elongated figures, the inverted

flower hats, and the lightness of execution suggest a knowledge of later

more refined chinoiserie design. The top is similarly decorated gently

built up into three dimensions using white size and fine plaster. Circa

1820.

|

China had developed a complex and sophisticated culture spinning over many

centuries. When the first British embassy set foot on its soil there were

more printed books and texts in China than the rest of the world put together.

The Chinese Emperor secure in the belief of the superiority of his people,

saw himself as the ruler of the world. All other nations were classed as

vassals. The delegates were looked down upon with indulgent curiosity.

The Chinese considered the English in their pompous but inelegant over dress

as little more than "monkeys in an opera" "prancing ponies" and their goodies

as quite irrelevant to their spiritually superior oriental way of life. Their

manner was considered crude and overbearing. They did not have the skill

of interesting them in anything.

On their part the English thought of the Chinese as backward. The British

sense of superiority was nurtured by the fact that England was stronger in

terms of military might and manufacture. It was inconceivable to them that

their industrial products would be scorned.

It is poignantly ironic that the Chinese invented gunpowder but did not exploit

its use in the manufacture of armaments to the extent the British had done.

To the Chinese, war, like everything else had a large element of art integrated

with it. The result was that their own invention was applied in the devastation

of so much of their own civilisation by a country whose government saw progress

merely in terms of industry, trade and war machines.

We only have to think of Chinese fireworks faced by English artillery guns

to realise the enormity of the chasm between the two cultures. There was

absolute mutual incomprehension. |

.thumb.JPG)

Important large Anglo Indian fully fitted sewing and

writing box of pyramided shape veneered with ivory profusely inlaid with

sadeli mosaic

Ivory was brought from Africa to India, where it was

turned into precious boxes which were then imported into Europe.

|

Subsequent attempts by England and to a lesser degree by Holland and other

European countries failed. The Chinese did not need anything from Europe.

In fact by the time of the second delegation in the second decade of the

nineteenth century, the monster which was originally created by the British

government, the Company opium merchants, sabotaged the proceedings by giving

the ambassadors wrong advice as to protocol. They did not wish their opium

trading to be diminished by alternative products.

In the meantime the East India Company was colonising large parts of India

on behalf of the English Crown. For England India was a gold mine in all

respects. It was nearer than China. It was fragmented by religion and system

of government. Different rulers administered different areas. A sophisticated

and ruthless power like England could easily manipulate and control them,

by playing the interests of one against the other. Systematic colonisation

and wealth extraction became policy.

The East India Company was the body responsible for most trading between

England and the East. They were the tea traders and they realised that their

own success depended on sustaining this trade according to the directives

of the government. |

|

Although it was supposed to exist as an independent entity, the East India

Company operated and administered the will of the British government. It

operated like government agencies and quangos operate now. It was an underhand

way for the government to flout international laws and agreements by setting

up contracts in circuitously devious ways and then wash its hands of blame.

The Company could not have been sustained without the support of the government.

On the other hand the government could not have earned so much revenue without

the overt criminality of the Company. When the Company ran into financial

trouble in India before the opium operation was up and running the British

government bailed it out. In 1784 the Prime Minister William Pitt divided

control of the Company between the Court of Directors and a Government Board.

The partnership was complete.

|

|

|

The East India Company set out to establish control of India by subterfuge

and force. In 1757 Robert Clive won a decisive victory at the battle of Plassey

which turned the tide very much in England's favour. The relationship between

England and India changed from that of trading co-operation to that of

Imperialism. The British ruled and the violence continued for several decades.

In 1773 Warren Hastings who was the Governor General excused the use of force

by the British as being compatible with "the customs of the country"!!!.

Ironically Clive himself died in England in 1774 from an overdose of laudanum.

The Company financed its own armed forces by revenue derived from growing

the opium poppy. The Company was given the monopoly for opium growing by

the British government and it set out to grow the crop with fanatical zeal.

Indian farmers were often forced to destroy other crops in order to grow

opium for the Company at below subsistence income. The Indian cotton industry

was devastated partly in order to boost the English cotton industry and partly

sacrificed to the new crop. Even English observes at the time commented on

how prosperous areas in India were destroyed for the sake of opium growing

which was destined for China.

|

|

|

Opium had been used both in India and China for many centuries in small

quantities for medicinal reasons. The British selling drive was something

quite different. It was a systematic and deliberate attempt to addict healthy

people to smoking the drug for the sole purpose of profit. It was carried

to China in the company's clipper ships, which then brought tea back to England.

When the going got tough with the Chinese complaining and refusing to sell

tea, the trading metamorphosed and was carried out by "independent" merchants,

or servants of the company acting privately. Different labels for the same

activity.

At first the Chinese court did not actively object to the importation. The

Imperial Court in Peking tried to impose an edict in 1729 forbidding the

use of opium for anything except medicinal reasons, but nothing much was

done about enforcing it. Cocooned by layers of officials and courtiers, the

consequences of the activities of their own merchants who negotiated the

buying of the drug took some time to penetrate the consciousness of the ruling

elite.

|

|

|

The addiction in China was well advanced before the scale of importation

was realised and measures were taken by the Chinese authorities. In 1815

an imperial edict from Peking forbade the traffic and use of opium. In 1819

a new emperor, Tao Kuang ascended the Imperial throne and hostilities between

the merchants and the authorities began to escalate. In the early 1830s the

emperor's own son died of opium addiction. The Chinese got tough. Vast amounts

of opium were destroyed in the East India Company's warehouses in Canton.

Complaints were dispatched to the government in England and to Queen Victoria.

The British government made disingenuous agreements with China not to allow

the East India Company to export opium whilst allowing the Company to have

the monopoly of growing it on the strict rule that the opium would only be

sold to merchants who would export it to China! Opium was for a time transported

in what were called "country ships" supposedly controlled by independent

merchants. The birth of modern political structures had arrived. The public

political stance was at complete variance with the real policy, which was

to serve the treasury at any cost.

|

|

|

For their part the merchants of the Company were finding other ways of disposing

their merchandise. They sailed their ships to the small island of Lintin

in the Canton estuary and with the help of corrupt and bribable officials

continued their business with the Hong merchants. The profits were vast.

It is difficult to have precise figures for such an illicit trade but records

suggest that up to 2000% profit could be made. At the beginning of the nineteenth

century only one to three thousand chests were sold; by the 1850s some twenty

thousand, which brought around £3,000,000; in the following decades

possibly three or four times as much.

By the end of the eighteen century England really needed the revenue from

tea to finance the Napoleonic wars. Figures suggest that in 1800 one tenth

of the import tax revenue derived from Tea. This is without the indirect

income from opium, which was vast. By 1833 when the tea trade was at its

peak it brought in up to four million a year, two thirds of what was needed

to keep the civil establishment including the Crown. Fiscal policy was

unsustainable without tea and opium.

|

|

|

n the meantime fortunes were made by exploiting opportunities offered both

by the war and the trading. The class system became more accommodating to

new money. Entrepreneurs mingled with the landed gentry in unholy alliances.

Great financial power was created which cemented the country's position as

an imperial power. The contribution to England's success of the two beautiful

plants the tea and the poppy cannot be overstated. Nor indeed can the misery,

which this trade unleashed on the world.

For a time in the early nineteenth century it looked as if the opium/tea

trade was going fine. However as more opium was grown, more tea was imported

and more people were muscling in for a share of the cake. Over expansion

brought about its own problems.

Bribery and discretion were keeping the trade going in China through the

Hong merchants until eventually the addiction and its repercussions became

too severe to be tolerated. By the 1830s the Chinese became more positively

active in their attempts to destroy the opium trade. Unfortunately their

beautiful swords and spears however artfully employed were no match for the

British military capability.

In 1833 Lord Napier was dispatched to China as the "Superintendent of Trade"

with the purpose of looking after British interests. He behaved in a provocative

bellicose manner, which justly earned him the epithet "laboriously vile".

He did not achieve much except to set up a warring agenda. By that time the

English were no longer seen as merely ridiculous. The "monkeys" were now

labelled the "foreign devils".

|

I

|

|

Serious hostilities started in 1839. Captain Elliot, a man with colonial

and naval experience had replaced Napier. His agenda was to pursue a policy

formulated since 1780 and lobbied for by the Company merchants, especially

Jardine and Matheson, of obtaining more trading rights for the British. In

1840 Men of War ships and armed steamers were prepared in India and dispatched

to China. The "Opium Wars" started in earnest. In 1841 China was forced to

cede Hong Kong as a trading base for English merchants. The young Queen Victoria,

who probably did not understand her new role as the first drug baron, was

not pleased. She thought her negotiators, namely Captain Elliot should have

extracted more! Her Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston was also vexed. So

the war went on for another year until the Treaty of Nanking was signed in

August 1842. The Company was compensated for opium burned by the Chinese

authorities and five more ports were open to the English merchants. There

was nothing more the Chinese could do to stop opium reaching their shores

in vast amounts.

England gained the odious distinction of being the first country to promote

drug addiction deploying military force. It also attained financial and thus

political supremacy through crop control. The repercussions of the opium

trade have left a legacy of poverty and addiction both in India and the Far

East and indirectly throughout the world.

However by the time England had taken hold of Hong Kong the opium and tea

trade had become more complex. Other countries were beginning to control

opium production in parts of India not under British control. More mobility

on the high seas weakened the English monopoly. The Company's monopoly in

India, which was no longer easily controlled, was taken away by the government

in 1834 under pressure from other interests. The floodgates were opened.

|

|

|

Some eminent politicians such as Gladstone had spoken out both against the

war and the opium trade. Writers and the press were beginning to inform the

public. Consciences were stirred. Tea for opium was no longer an easy option.

The obvious solution was to set up tea production in India and Ceylon. It

was no longer possible to charge exorbitant duties on tea, nor was it possible

to keep up the pretence of its rarity. The trading philosophy substituted

quantity for exclusivity and the vast plantations, which we now know, were

set up to supply the world with tea. The tea was of course British controlled

and it made another round of fortunes. In 1838 the first tea from India reached

London from Calcutta but it took more than twenty years before Indian tea

really began to be imported in any quantities. By 1883 the scales had tilted:

two thirds came from India and Ceylon.

Ironically the turning point for tea was synchronous with the defeat of China

in the Opium Wars. Since the middle of the nineteenth century tea became

increasingly plentiful. In the twentieth century appreciation of quality

all but disappeared and it is only in the last few years that there is a

move away from the ubiquitous tea bag back to fine teas. Once again there

is recognition of the therapeutic properties of tea, something which the

Chinese have known for thousands of years and which was one of the qualities

first extolled when tea was first introduced.

Now that it is no longer interlinked with opium tea will perhaps come to

a full circle once again. Appreciated for the fine beverage it can be when

planted nurtured and gathered with care it does not need criminal interests

to promote it.

|

|

© 1999-2008 Antigone Clarke and Joseph O'Kelly

|